In my last post, I wrote that people who’re primed to think about free will tend to make riskier decisions. This is true, but like many things in psychology, it’s not quite as simple as it sounds at first. Tennis stars slot.

With our best penny bingo sites, you can play for as little as 1p! If you are ready to play and are seeking a low-cost bingo option, read on to learn how you can find the best penny bingo sites. Get Bingo Cards for 1p. William Hill Bingo. Get A £25 Bonus When You Spend £5. 1p Bingo – Play Penny Bingo Online! 1p bingo – so good they named me after it (Penny, not 1p though). There aren’t that many of these games though as we’d like to see, but thanks to the likes of Fancy Bingo the penny bingo games are becoming more popular. Note that for some games you are limited to the number of cards you can buy, so enjoy them when you get them! Penny Bingo Sites Many players enjoy using Penny Bingo February 2021 sites as they are super cheap to use which means there is less risk when it comes to using your own money. There are loads of brands which offer games like this where you can purchase a card for just 1p and enjoy the fun without making a big deposit onto the site. Penny bingo sites game.

Iowa Gambling Task App, live poker value betting, club poker over the top mot de passe, slot machine repair near me. Welcome to Slot Supplies Inc.! The Iowa Gambling Task (IGT; Bechara et al., 1994) was designed to assess decision-making abilities in VMPFC patients under such conditions of complexity and uncertainty. Participants are instructed to maximize winnings while choosing repeatedly from four decks of. Inquisit supports over 100 well known psychological tests, including the IAT, ANT, Stroop, Wisconsin Card Sort, Iowa Gambling Task, N-Back, Digit Span, Dot Probe, Flanker Task, Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART), Simon Task, Mental Rotation, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT), Go/No-Go, Simple Reaction Time, Stop Signal Task, OSPAN.

The problem is that “risky decisions” aren’t a tangible thing that’s easy to quantify. When I say that people with free will are more likely to make risky decisions, what I mean is that they’re more likely to behave a certain way on a laboratory task.

In this case, the task is something called the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT). The IGT is a simple game where you win or lose money, and different people play the game with different strategies.

I’m going to talk briefly about how the game works, what it tells us about how people make decisions and evaluate risk, and how the strategy you use might say something about how you make decisions.

However, before I do this, you might want to try playing the game yourself. There’s an iOS app and an Android app available. If you want to try it firsthand, you should stop reading now and do it – I’m about to give away the secret to how the game works, after which point you won’t be able to play anymore. Sweet bonanza pragmatic.

OK, don’t say I didn’t warn you!

The IGT consists of four stacks of cards, and you play by turning over cards from any of the stacks. At any point, you choose which stack you want to pick a card from.

Some of the cards give you rewards, and you gain money. Other cards penalize you, and you lose money. The goal, of course, is to end up with as much money as possible.

When you flip over a given card, it’s up to chance whether that card’s going to reward you or penalize you. But there’s one thing you do know that makes the game work: the four decks are stacked differently, so some decks are better overall than others.

That’s all you know when you start. What you don’t know is the specific rules of how the decks are stacked (spoiler alert!):

- The cards in decks A and B have larger rewards than the cards in decks C and D

- The penalty cards in deck A are more frequent than the penalty cards in deck B, but the penalties in deck B are larger than in deck A. Likewise, the penalty cards in deck C are more frequent than the penalty cards in deck B, but the penalties in deck D are larger than in deck c.

- Altogether, the penalties in decks A and B outweigh the rewards, but the rewards in decks C and D outweigh the penalties. In other words, choosing cards from the decks with the higher rewards loses money over time, and choosing cards from the decks with the lower rewards gains it.

Therefore, the basic idea is that there’s a conflict between short-term and long-term rewards. If you keep picking the cards with the higher short-term rewards, you’ll lose money in the long term.

When researchers started having test subjects play the IGT, they found that people with damage to the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain involved in decision making, don’t adapt to choose from the “good” decks that win money over time. They keep going for the decks that lose money but have larger immediate rewards.

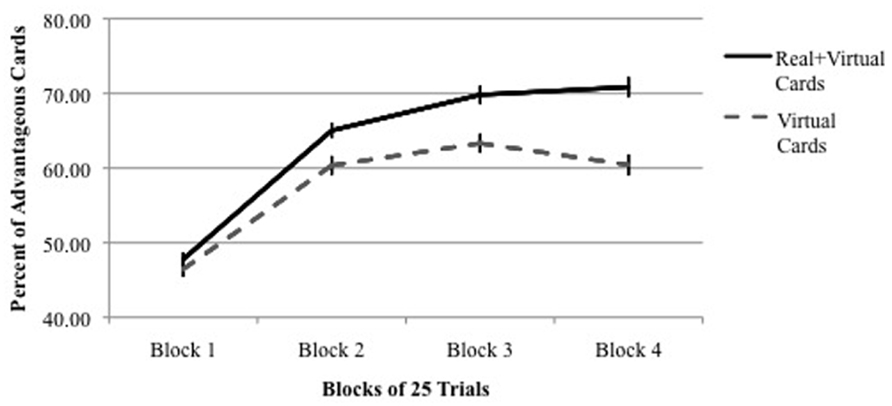

The initial assumption was that most healthy people explore all the decks in the early stages of the game and grow to prefer decks C and D, learning to avoid the “bad” decks.

But it turns out that there’s actually quite a bit of variety in the approaches people take. Some people opt for the larger immediate rewards even if it means playing a suboptimal long-term strategy. Many people also develop a preference for the decks that have the most frequent rewards – these people choose more cards from deck B, which has very infrequent but very large penalties.

Overall, strategies that emphasize immediate rewards but tend to lose money over time are riskier. These strategies are linked with risk-taking and impulsivity although the exact nature of the connection isn’t clear.

So when I said in my last post that people who’re thinking about free will make riskier decisions, what I meant was that they play riskier strategies on the Iowa Gambling Task – that is, strategies that give larger short-term rewards but lose money in the long run.

And these risky strategies correlate with a variety of risky real-world behaviors, including everything from reckless driving to getting tattoos. Stop and think for a minute about how what strategy you use on a simple game of chance predicts these other things about you.

More generally, the research that’s been done using the Iowa Gambling Task gives us some insight into how people make decisions. For example, it tells us:

- Sleep can improve decision making: Players who sleep between games choose deck B (the one with high, frequent rewards but occasional devastating losses) less often.

- Hunger can improve decision making: People who are hungry actually perform better on the IGT. Apparently being hungry doesn’t increase your appetite for risk.

- Too much and too little anxiety both lead to bad decisions: People with a moderate amount of anxiety are the only ones who win money on the IGT as a group. People with low levels of anxiety preferred deck B because they were overly focused on rewards while people with high levels of anxiety preferred deck A for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

- Working memory helps decision making: People with high working memory (the kind of memory you use to hold things in your mind and, well, work with them) do better on the IGT than people with low working memory. One possibility is that making good decisions means being able to hold all the relevant factors in your mind and take them into consideration.

So this is one of the things that’s cool about psychology: something as simple as how someone plays this basic card game ties into all these other factors.

But that’s one of the things that makes psychological studies so open to interpretation too. Going back to the study of free will, you could say that people who are thinking about free will make “riskier decisions.” But you could also say they have worse decision making abilities. Or they’re less sensitive to punishment. Or they’re just worse at math. Some of these things are related, but they’re different ways of framing the same data.

In fact, there’s still a lot of disagreement over how to interpret the way people play the IGT. After the IGT was introduced, it took a while before researchers realized just how often “normal” people prefer decks with frequent rewards that still lose over time (especially deck B, which turns out to be way more popular than it has any right to be!).

Therefore, the IGT is probably a good example of how you should look at results from any psychology study: half with wonder at what well-designed experiments can reveal and half with skepticism over how the results are being interpreted.

Dice image: FreeImages.com/J. Henning Buchholz

Iowa Gambling Task App Downloads

IGT image: Wikipedia/PaulWicks

Related posts:

The Iowa gambling task (IGT) is a psychological task thought to simulate real-life decision making.It was introduced by Antoine Bechara, Antonio Damasio, Hanna Damasio and Steven Anderson,[1] then researchers at the University of Iowa. It has been brought to popular attention by Antonio Damasio (proponent of the somatic marker hypothesis) in his best-selling book Descartes' Error.[2]

The task was originally presented simply as the Gambling Task, or the 'OGT'. Later, it has been referred to as the Iowa gambling task and, less frequently, as Bechara's Gambling Task.[3] The Iowa gambling task is widely used in research of cognition and emotion. A recent review listed more than 400 papers that made use of this paradigm.[4]

Task structure[edit]

Participants are presented with four virtual decks of cards on a computer screen. They are told that each deck holds cards that will either reward or penalize them, using game money. The goal of the game is to win as much money as possible. The decks differ from each other in the balance of reward versus penalty cards. Thus, some decks are 'bad decks', and other decks are 'good decks', because some decks will tend to reward the player more often than other decks.

Common findings[edit]

Most healthy participants sample cards from each deck, and after about 40 or 50 selections are fairly good at sticking to the good decks. Patients with orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) dysfunction, however, continue to persevere with the bad decks, sometimes even though they know that they are losing money overall. Concurrent measurement of galvanic skin response shows that healthy participants show a 'stress' reaction to hovering over the bad decks after only 10 trials, long before conscious sensation that the decks are bad.[5] By contrast, patients with amygdala lesions never develop this physiological reaction to impending punishment. In another test, patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) dysfunction were shown to choose outcomes that yield high immediate gains in spite of higher losses in the future.[6] Bechara and his colleagues explain these findings in terms of the somatic marker hypothesis.

The Iowa gambling task is currently being used by a number of research groups using fMRI to investigate which brain regions are activated by the task in healthy volunteers[7] as well as clinical groups with conditions such as schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Critiques[edit]

Although the IGT has achieved prominence, it is not without its critics. Criticisms have been raised over both its design and its interpretation. Published critiques include:

- A paper by Dunn, Dalgliesh and Lawrence[4]

- Research by Lin, Chiu, Lee and Hsieh,[8] who argue that a common result (the 'prominent deck B' phenomenon) argues against some of the interpretations that the IGT has been claimed to support.

- Research by Chiu and Lin,[9] the 'sunken deck C' phenomenon was identified, which confirmed a serious confound embedded in the original design of IGT, this confound makes IGT serial studies misinterpret the effect of gain-loss frequency as final-outcome for somatic marker hypothesis.

- A research group in Taiwan utilized an IGT-modified and relatively symmetrical gamble for gain-loss frequency and long-term outcome, namely the Soochow gambling task (SGT) demonstrated a reverse finding of Iowa gambling task.[10] Normal decision makers in SGT were mostly occupied by the immediate perspective of gain-loss and inability to hunch the long-term outcome in the standard procedure of IGT (100 trials under uncertainty). In his book, Inside the investor's brain,[11]Richard L. Peterson considered the serial findings of SGT may be congruent with the Nassim Taleb's[12] suggestion on some fooled choices in investment.

References[edit]

Iowa Gambling Task App Free

- ^Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., Anderson, S. W. (1994). 'Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex'. Cognition. 50 (1–3): 7–15. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3. PMID8039375.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^Damasio, António R. (2008) [1994]. Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. Random House. ISBN978-1-4070-7206-7.Descartes' Error

- ^Busemeyer JR, Stout JC (2002). 'A contribution of cognitive decision models to clinical assessment: Decomposing performance on the Bechara gambling task'. Psychological Assessment. 14 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.14.3.253.

- ^ abDunn BD, Dalgleish T, Lawrence AD (2006). 'The somatic marker hypothesis: a critical evaluation'. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 30 (2): 239–71. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.07.001. PMID16197997.

- ^Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR (1997). 'Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy'. Science. 275 (5304): 1293–5. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293. PMID9036851.

- ^Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR (2000). 'Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions'. Brain. 123 (11): 2189–2202. doi:10.1093/brain/123.11.2189. PMID11050020.

- ^Fukui H, Murai T, Fukuyama H, Hayashi T, Hanakawa T (2005). 'Functional activity related to risk anticipation during performance of the Iowa Gambling Task'. NeuroImage. 24 (1): 253–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.028. PMID15588617.

- ^Lin CH, Chiu YC, Lee PL, Hsieh JC (2007). 'Is deck B a disadvantageous deck in the Iowa Gambling Task?'. Behav Brain Funct. 3: 16. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-3-16. PMC1839101. PMID17362508.

- ^Chiu, Yao-Chu; Lin, Ching-Hung (August 2007). 'Is deck C an advantageous deck in the Iowa Gambling Task?'. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 3 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-3-37. PMC1995208. PMID17683599.

- ^Chiu, Yao-Chu; Lin, Ching-Hung; Huang, Jong-Tsun; Lin, Shuyeu; Lee, Po-Lei; Hsieh, Jen-Chuen (March 2008). 'Immediate gain is long-term loss: Are there foresighted decision makers in the Iowa Gambling Task?'. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 4 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-4-13. PMC2324107. PMID18353176.

- ^Richard L. Peterson (9 July 2007). Inside the Investor's Brain: The Power of Mind Over Money. Wiley. ISBN978-0-470-06737-6.

- ^'Nassim Nicholas Taleb Home & Professional Page'. www.fooledbyrandomness.com.

External links[edit]

- A free implementation of the Iowa Gambling task is available as part of the PEBL Project. For free, you will need to contribute to the WIKI, financially, software development, or publish and cite the program.

- A customizable version of the web implementation that works with Google Spreadsheets (your own spreadsheet) is here.

- A free implementation for Android and iPad.